Like almost anything in Toledo, marzipan also has a legendary origin inspired by the city’s intense history. Let’s narrate a few curiosities and legends that accompany the sweet Christmas par excellence not only in Toledo, but in many other parts of Spain.

Index of Contents

The legendary origin of marzipan in Toledo

José H. Polo (” Odiel”. Huelva 24-XII-1966) alludes but in an ironic tone to the nuns of San Clemente by adding a miraculous variant to the invention of marzipan: “There was, he says, a distant period of famine in Toledo.

It culminated in a period in which wars, drought and epidemics had depopulated the fields and devastated the places.

Certain nuns asked their patron saint to help them find a way to alleviate hunger, and it seems that the saint, no doubt an aficionado of the delicacies of baking, must have recommended the marzipan, which was not so called at the time.

It was a luxury item, but the nuns had to find a way to produce it cheaper, and in marzipan the remedy for the starving arose. It was for them like bread. And from here some imaginative people deduced that its present name comes from it.

When did marzipan begin to be made in Toledo?

Indications are that it was not in Toledo that this famous sweet was made. The exact date on which marzipan began to be made in our city is not very clear either, since centuries before it was already known in Italy and the Arab countries.

If we investigate the origin of marzipan we find a chronicle that tells us how Muslims imported this rich delicacy in the eighth century when they invaded the Peninsula, although it is likely that they were sweet in various variants with almonds and not specifically called “marzipan” or some similar spelling.

But in Toledo, as it usually happens, we have another version of ours that explains how the creation of the candy was created.

The remembered chronicler Don Clemente Palencia already told decades ago a certain legend from Toledo that said that the Cistercian convent of San Clemente, founded in the 12th century, was the cradle of marzipan in the city. The Bernardas nuns possessed a large quantity of almonds among their possessions and therefore the almonds they received were elaborated with a proportional quantity of sugar to transform them after going through the oven into a paste that could last several months.

Legend has it that the nuns of the convent of San Clemente, to face the hunger when the city was besieged by the Arabs, with almonds and sugar crushed with a mallet made a “bread of mallet”.

Outside the legends, it is true that there is a cookery book dated 1577 that was printed in Toledo and whose author was Ruperto de Nola (cook of Fernando de Nápoles) in which there is a recipe for making marzipan.

Surely you are also interested: Photographs of Toledo 100 years ago and now Cover of the Museum of Santa Cruz made in marzipan. Photo: José Torres

What’s the recipe for marzipan?

Toledano’s sweet par excellence is undoubtedly marzipan; its simple (and ancestral) recipe based on almonds and sugar has made it one of the star gastronomic resources of the Imperial City.

The recipe for Toledan marzipan is very simple and has not been altered for hundreds of years, with totally natural ingredients: almonds (raw, peeled and ground), sugar, eggs and sometimes a touch of pure bee honey. (See marzipan recipe)

The mixing and kneading of these simple ingredients results in a fine, compact dough. This dough is shaped into several curious figurines, painted with egg and baked at high temperature producing a real delicacy appreciated not only in Toledo, also around the world.

Almonds are the main ingredient of the paste, the composition of which must be a majority or at least 1:1, i.e. 50 % of the total weight. The almonds used are of sweet varieties, repelled and with a minimum fat content of 50 %.

On the other hand we find that the guild of confectioners that is organized and structured in the seventeenth century, made its ordinances in 1613 and indicates in clause 16 the following:

” We order that the marzipans that are made are jaropados e dealmendras de Valencia e de azúcar blanco e no other way or else on pain that the opposite ficiere, incur the penalty of a thousand maravedís each time…”

Therefore already in this century the production and consumption of marzipan was more than consolidated since either the Muslims or the nuns of San Clemente had introduced it in the city centuries ago.

Arriving in the nineteenth century in the Diario de Madrid of 1817, it is reported that in a certain confectionery called the Toledano located on Calle del Príncipe, marzipan was made “as made in the city of Toledo,” remarking – once again – that the best and most famous marzipan was made, as continues to happen in the city of Toledo.

The importance of marzipan in Toledan gastronomy

At present, it is sold intensively throughout the year and it is very common to see tourists carrying bags of well-known confectioneries producing marzipan in the city. In the run-up to Christmas, online sales of Toledo’s different brands soar, and production efforts are intensively reinforced to supply the entire market.

Marzipan also has a frequent presence in the gastronomy of Toledo, not only as a dessert or occasional sweet, but also as an ingredient in the most refined confectionery recipes, which accompany the succulent lunches and dinners offered in the numerous restaurants of the city.

It is very common to see in the menus and menus of Toledo at least one dessert made with marzipan from the city.

Confitería Santo Tomé in Zocodover.

Confitería Santo Tomé in Zocodover.

What is certain is that the degree of excellence achieved in this product in the city is very remarkable, and is currently exported to many countries, as well as being a delicacy much appreciated by the Toledo. In occasions they have been reproduced even known monuments toledanos using exclusively marzipan.

Recently, a Guinness record was presented with the largest marzipan Quixote in the world, elaborated by Confitería Santo Tomé.

Presentation of Quixote made in the world’s largest marzipan.

Why are marzipan eels made in Toledo?

Photo: Elisue on Flickr.com

Photo: Elisue on Flickr.com

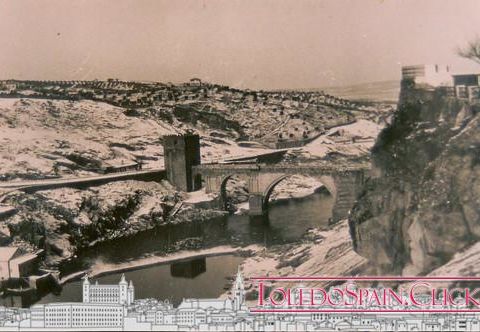

Some chroniclers say that exquisite eels were bred in the Tagus river (when the river had a flow and was not contaminated) and that, when it disappeared in the 19th century, the Toledo confectioners replaced them with marzipan eels.

Where to buy good marzipan in Toledo?

In Toleod there are many places to get marzipan at any time of the year, but especially at Christmas time. Here are some of the most recognized:

- Santo Tomé : With several workshops scattered throughout the city. The most famous, the establishments of Zocodover and the Rue Saint-Tomé.

- Casa Telesforo : very close to Zocodover.

- Mazapanes Conde : in the street of the Bulls. A little hidden, but of great quality.

Portada Convento San Clemente in Toledo

Portada Convento San Clemente in Toledo

Convents that make and sell marzipan:

- Convent of San Clemente. Here is the legend that originated the marzipan… In the street San Clemente, 1.

- Convent of Saint Anthony of Padua. In Santo Tomé Street.

- Convent of Jesus and Mary. Outside the old town, on Avenida de Francia.

- Convent of Santo Domingo el Antiguo. In addition to admiring their Grecos, you can buy marzipan and other sweets.

- Convent of Santo Domingo el Real.

Other curiosities about marzipan in Toledo:

- The Emperor Charles V, already retired in the Monastery of Yuste, received marzipan that the nuns of St. Clement punctually sent to him, being one of the gifts that he liked most of all he received in his retreat.

- In the cigarette of Minors don Gregorio Marañón always gave his guests a marzipan dessert.

- During the Civil War, when sugar was rationed, confectioneries had to resort to dried figs as a substitute to sweeten the pasta.

- The piece of breadcrumbs with which bishops used to wipe their anointed fingers of the oil used to administer baptism to princes was wrapped in a cylindrical sponge cake, pierced in the center which, curiously, was called “marzipan“.