The Well and the Pendulum, The Pit and the Pendulum, written in 1842, is one of Edgar Allan Poe’s best-known stories. We recommend its reading in absolute tranquillity, with little light, and with the certainty that we are witnessing one of the most terrifying stories that literature has ever given.

The uncertainty before a near death produces in this story an anguish that only Poe is able to define.

The dungeon, where the prisoner is being held is in Toledo, as could not be less: “…a thousand vague rumours about the horrors of Toledo were massively confused in my memory”.

Impia tortorum longas hic turba furores sanguinis innocui, non satiata, aluit, sospite nunc patria, fracto nunc funeris antro, mors ubi dira fuit vita salusque patent.

(Composite quartet for doors of a market that had to be erected at the Jacobins Club in Paris.)

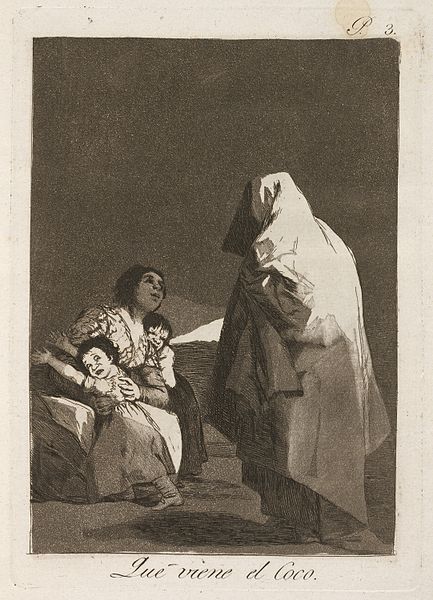

I was exhausted, exhausted until I could no longer, by that long agony. When they finally untied me and I was able to sit down, I noticed that I was losing consciousness. The sentence, the appalling death sentence, was the last clearly accentuated sentence that reached my ears. Then, the sound of the voices of the inquisitors seemed to me to be extinguished in the indefinite hum of a dream.

The noise provoked in my spirit an idea of rotation, perhaps because I associated it in my thoughts with a millstone.

But it didn’t last long, because suddenly I didn’t hear anything else. But for a while I could see, but what a terrible exaggeration! I saw the lips of the judges dressed in black: they were white, whiter than the sheet of paper on which I am writing these words; and thin to the grotesque, thinned by the intensity of their harsh expression, of their inexorable resolution, of their rigorous contempt for human pain.

I saw that the decrees of what Fate represented for me were still coming out of those lips. I saw them twist into a mortal phrase, I saw them pronounce the syllables of my name, and I shuddered to see that the sound did not follow the movement.

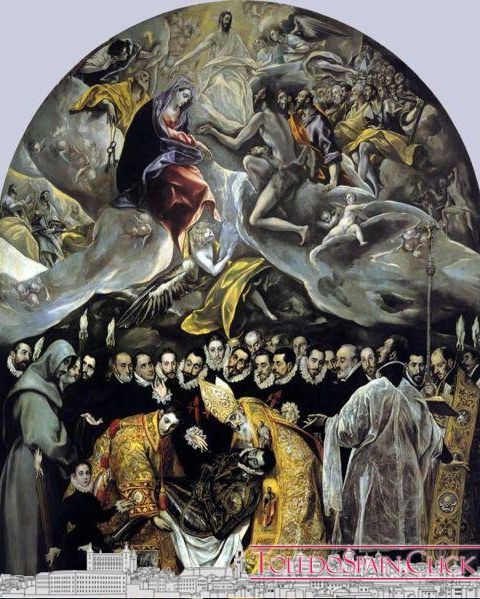

During several moments of frantic fright I also saw the soft and almost imperceptible undulation of the black hangings which covered the walls of the room, and my sight then fell on the seven large axes which had been placed on the table. They took for me, at first, the aspect of charity, and I imagined white and slender angels who were to save me.

But then, and suddenly, deadly nausea invaded my soul, and I felt that every fiber of my being shuddered as if it had been in contact with the thread of a galvanic battery. And the angelic forms became insignificant spectres with the head of a flame, and I clearly understood that I should not expect any help from them.

Then, like a magnificent musical note, the idea of the ineffable rest that awaits us in the tomb was insinuated into my imagination. It arrived softly, furtively; I think I needed a great deal of time to appreciate it fully.

But at the very moment when my spirit began to feel this idea clearly, and to caress it, the figures of the judges vanished as if by magic; the great axes were reduced to nothing; their flames were extinguished completely, and the blackness of darkness ensued; all sensations seemed to disappear as in a mad and precipitated plunge of the soul into Hades.

And the Universe was only night, silence, immobility.

He was vanished. But, nevertheless, I cannot say that I would have lost consciousness altogether. The one I had left, I won’t try to define it, or even describe it. But, in the end, everything was not lost. In the midst of the deepest sleep… no! In the midst of delirium… no! In the midst of fading… no! In the midst of death… no! If it were otherwise, there would be no salvation for man. When we wake up from the deepest sleep, we break the spider’s web of some dream. And yet, a second later, this fabric is so delicate that we do not remember dreaming.

There are two degrees, on returning from fainting to life: the feeling of moral or spiritual existence and that of physical existence.

It seems probable that if, on reaching the second degree, we had to evoke the impressions of the first, we would again find all the eloquent memories of the transmundane abyss. And what is that abyss?

How, at least, can we distinguish its shadows from those of the grave? But if the impressions of what I have called first degree do not come again to the call of the will, nevertheless, after a long interval, do not appear without being solicited, while wondering where they come from? He who has never fainted will never discover strange palaces and singularly familiar houses among the burning flames; he will not be the one who contemplates, floating in the air, the melancholic visions that the vulgar cannot glimpse, he will not be the one who meditates on the perfume of some unknown flower, nor the one who will be lost in the mystery of some melody that has never attracted his attention until then.