Most painters used these so-called ‘hieroglyphics’ in their paintings to let us see certain subjects that in most cases their symbolism was forbidden by the Church or were frowned upon by kings, nobility or even the common people. In Toledo we were lucky enough to have ‘El Greco’ who knew how to deal with the censorship of the time.

We will never be thankful enough that the rigid and austere Philip II did not like those nudes that ‘El Greco’ painted in his oils or those strange symbols. In this way he was able to come to Toledo and carry out most of his work in our city.

The Cretan painter had to walk with lead feet in all his artistic expressions captured in his canvases because he had censors that watched him very closely and either seemed immoral or sometimes argued that some pictorial details did not conform to the evangelical reality, as if when painting a picture had to stick obligatorily to the Holy Scriptures.

In our days this has no reason to be but in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries for much less people were sent to the stake.

Born our artist in Crete where he was a famous master iconographer of the post-Byzantine style usual on the island, he would spend ten years in Italy, first in Venice where he was influenced by Titian and Tintoretto and later in Rome where the study of Michelangelo’s mannerism would be constant in his life.

Therefore that mixture of styles of these Titans of painting would crystallize in the ‘genius’ that by circumstances of the life would come to Toledo where the painter and the city already I have commented many times that they would form a perfect symbiosis.

I’m sure you’re also interested: El Greco de Toledo. Get to know Toledo 16

It is supposed that El Greco earned money and lived well in Toledo, but he had not few lawsuits with the Church and with various institutions, because sometimes his painting was not well understood in traditional Catholic culture and other times for the appraisal of his works.

To avoid useless clashes, especially with the Church, ‘El Greco’ left us quite a few signs in his paintings which were called ‘hieroglyphics’ by Cesare Ripa in 1593. I cannot enumerate them all because the article would be too long but I will try to break down the most significant that I have not discovered of course, but scholars and scholars of the work of our painter par excellence.

St. John the Baptist, El Greco (Between 1577 and 1579) Source: Wikimedia (CC)

St. John the Baptist, El Greco (Between 1577 and 1579) Source: Wikimedia (CC)

According to Juan Esteban Lorente there are hieroglyphics for ‘absence’, in this way in the altarpiece of Santo Domingo el Antiguo, we see how San Juan Bautista points with his finger towards the ground, but what does he point out: the missing figure is the hieroglyph and here the painter makes us understand the famous phrase of San Juan when he saw Jesus approaching and said pointing out: “This is the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world”… We lack the Lamb.

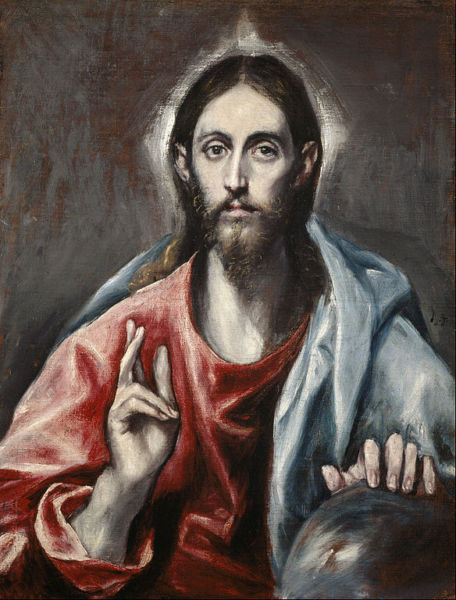

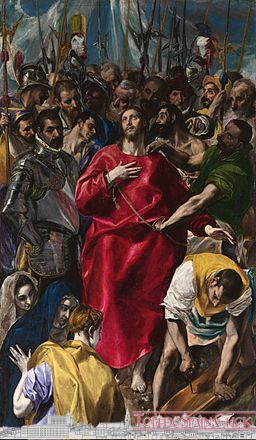

The Expoliation, by El GrecoIn The Expoliation of the Cathedral of Toledo, the figure that we lack is precisely Saint John, because according to the Sacred Scriptures he was present in the Passion of the Lord, but here the hieroglyph is the same Christ because at the hour of expiration Jesus says to Mary and John: “Woman there you have your son, Son there you have your mother” therefore Saint John is represented in the same Jesus Christ as Son of Mary.

The rabble dresses Jesus with a red tunic and a crown of thorns to mock Him, treating Him as King, then it is torn off; for in this tunic we can see the indication of what would later be the chasuble with which the priest is dressed for the sacrifice of the Mass, another symbol represented in the picture.

The Adoration of the Shepherds (El Greco)

The Adoration of the Shepherds (El Greco)

There are hieroglyphics for ‘excess’ and here we can see it in The Adoration of the Shepherds, a picture of his late production that was going to serve for his family pantheon.

Here ‘El Greco’ portrays himself as an old man and we distinguish a bull figure that represents the evangelist St. Luke, who is the only one who relates the fact of the adoration of the shepherds.

As Marian hieroglyphics we could point out how in various paintings of the Immaculate or the Annunciation, in one painting we have a fountain meaning that Jesus would be born from the Fountain of Mary (Fountain of Salvation) and in another offering us a bush as a symbol of the Old Testament: “The bush burned and did not burn, the Virgin Mary a maiden and pregnant”.

The fountain and the bush symbolize Mary.

The prophet Elisha narrates how a lumberjack falls the axe to the river Jordan and to recover it throws a tree into the river, miraculously the iron leaf of the axe comes out afloat, (fact narrated in the II book of Kings) well, in the Baptism of Christ of the Prado Museum, we see this scene, the hieroglyphic is Christ represented in the wood of the Passion, humbly I want to understand that when the wood sinks into the water makes humanity rise fallen by the sin represented in the axe.

El Greco – The Penitent Magdalene – Google Art Project

El Greco – The Penitent Magdalene – Google Art Project

There is no need to explain why El Greco in various paintings The Magdalene is always depicted with a branch coming out of some wall, as is St. Peter for having denied it both in Jerusalem and in Rome. Therefore a whore or a sinner was always represented with a branch in hand or on a wall.

“The gentleman with the hand on the chest.” El Greco, 1578-1580. Prado Museum. Fountain: Wikimedia.

But what strikes us most in the paintings of ‘El Greco’ are the hands and of course the fingers, here it would be very long to explain all their meanings, because sometimes they are of supplication, in others they express the miracle of salvation or blessing with the hand extended towards the sky, other times we feel like dialogue or letting do as in The Garden of Olives, but when we are most struck by the two fingers united, the heart and the ring on the chest is because they want to tell us: “I say it and I do it from the heart”, cases of El Expolio and El Caballero de la mano en el pecho.

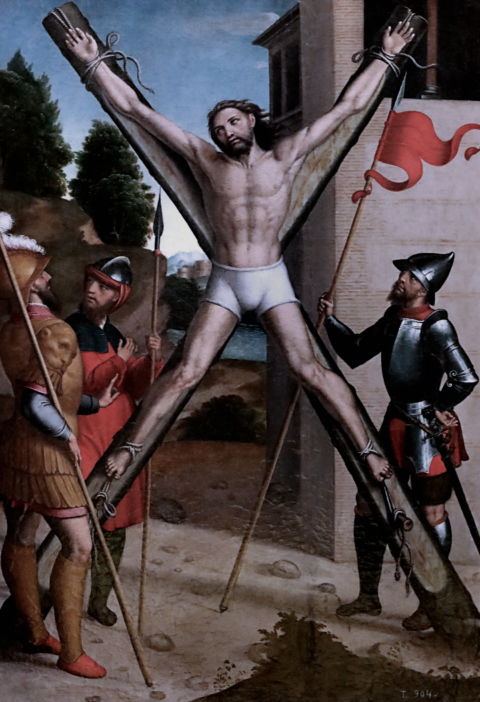

I can’t get any longer, but in pictures like the Lady of the Armiño, The Burial of the Lord of Orgaz, the Martyrdom of Saint Maurice and others, there are many more curious hieroglyphics that might give for another article.

Of course I want to tell you that thanks to Vicente Encina, in researching these paintings of ‘El Greco’ I have been impressed.

There is no doubt that, as I always say, he was a genius and I will not tire of saying it, an expert in many matters as he shows us with the knowledge he had of course of the Sacred Scriptures, but also of all the authors dedicated to the meaning of the different symbols and esotericism that through the years were captured in the different treatises known at the time.

Once again I apologize for the length of the publication, but I think it was worth it and if you will allow me there will be a second part.