He died in absolute destitution, accused by the Inquisition and with enormous debts… It could be the description of any resident of Toledo during the Renaissance, but in this case we are talking about one of the greatest engineers who resided in our city.

Juanelo Turriano built an “artifice” that facilitated the rise of water for human consumption from the Tagus to Toledo. We inaugurate the section “Toledanos Characters”.

Juanelo Turriano is a character closely related to the city of Toledo, comparable to the figure that Leonardo Da Vinci meant for Italy in the Renaissance and very little valued by our culture.

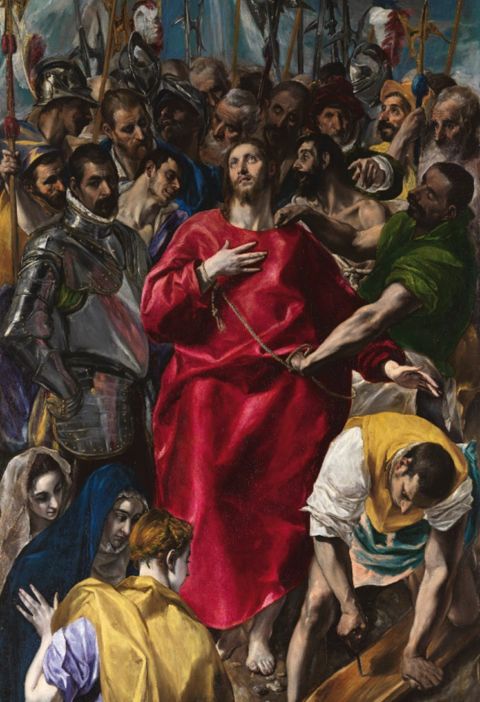

Few people in Spain know that Juanelo was one of the pioneers in creating a complex system of ascending waters saving a strong slope, as we will see next. Juanelo, along with “El Greco” is one of the Renaissance Toledan characters who stood out and have reached us. Both were not Toledans, not even Spaniards by birth, but their works have lasted until us in a notorious way.

Turriano was born at the beginning of the 16th century in the Lombard city of Cremona, and his real name was Ianellus Turrianis, or Giovanni Torriani, unlatinized.

His skills as a watchmaker and mechanic interested Charles I, who brought him to Spain to put into operation a large collection of astronomical clocks with which he distracted his last days in the monastery of Yuste.

There he built the well-known “crystalline “that made him famous in his time. Later, when the Emperor died, he went to the service of Philip II, on horseback between Toledo and the Escorial, the latter under construction. At some point was even claimed by the pope Gregory XIII to participate in the renewal of the current calendar (Gregorian).

During the time that Juanelo spent in Toledo, he devised in his own way a way to supply water to the city, especially to the palaces that the emperor had in the area of the present Alcázar.

During the time that Juanelo spent in Toledo, he devised in his own way a way to supply water to the city, especially to the palaces that the emperor had in the area of the present Alcázar.

Certainly before, ways of bringing this water had already been devised, in the “Roman way”, with an impressive aqueduct on the Tagus for the most complex area (unfortunately already destroyed), or with the traditional “azacanes “(water carriers from the Tagus using mules), or with unhealthy wells contaminated by excess waste water.

Prior to the construction of the “famous artifice”, some German engineers built a “water building” to ascend the precious element by mechanical means.

But the pipes burst under the pressure of water… Shortly afterwards, other Flemish technicians again tried to find a solution to the water carried inside the Toledo wall, but failed after 865 days of work.

Juanelo, after observing these attempts, and already at the age of 65 presents the king and the city with an ambitious project to raise this water to the fortress.

In 1565 the contract of adjudication is signed between the king, the city and Juanelo, in which it is detailed that the works will run for account of this last one, but that if it works according to the projected thing, 8000 ducats will be paid to him, after 15 days of the arrival of the water to the Alcazar and other 1900 ducats of perpetual income each year, running to his coasts the maintenance of the gadget”.

I’m sure you’ll also be interested in: Legend of the Toledo Marzipan

On February 23, 1569, Juanelo delivers his “artifice” in full performance even surpassing by 50% what was projected. But after the completion of the work and the arrival of water at the Alcazar, the city decided not to pay a single duchy claiming that they did not get even a drop of water, as all remained in the Alcazar.

The solution to the conflict consisted in the construction of a second artifice to supply the whole city, after six years of lawsuits. In 1581, this second artifice, attached to the second one, was in operation, and the building costs were borne by the King.

Juanelo’s “artifice” was one of the greatest attractions of the time in Toledo, known and admired throughout Europe.

Ambrosio de Morales left a fairly approximate description of what the artifice was, which has allowed a certain level of reconstruction of the apparatus to scale.

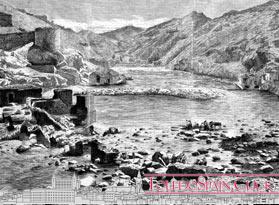

Unfortunately, and as is often the case in Toledo, from 1617 onwards and when Juanelo’s descendants abandoned the care of the building and it stopped, he suffered a series of lootings in his materials that left the factory unrecognizable. The last remains were taken in the 18th century to the Real Sitio de Aranjuez, where they needed pipes to supply water. Nowadays, one can hardly intuit the place that the first level of the “artifice” occupied in the course of the Tagus. All that remains are the machons of what could have been one of the greatest engineering works of all time.

This magnificent work carried out by Juanelo, near the Alcántara bridge, involved ascending the water by a total gradient of 100 metres and a horizontal route of 300 metres, with an average gradient of 33%.

It was made up of a dam and two driving wheels at river level, six intermediate stations – aqueduct raft, Forge gate, Carmen passageway, Santiago plain, Pavones corral and Alcázar esplanade – and a total of 192 buckets arranged in tilting armor and grouped into 24 intermediate units or turrets.

The driving force was transmitted by means of alternating motion connecting rods. With all this, a flow rate of 11.8 litres per minute was achieved, which is equivalent to 17,000 litres of water every 24 hours.

According to some authors, the device would also be quite fragile, since most of it was made of wood. Only Augsburg (1548), prior to Toledo, London (1582) and Paris (1608) had a mechanism similar to that of our city.

Interesting are the granite monoliths (in the form of columns) that at first went to form part of this building but finally remained halfway.

Interesting are the granite monoliths (in the form of columns) that at first went to form part of this building but finally remained halfway.

Extracted from a quarry in the Toledo locality of Orgaz, “los postes de Juanelo” (Juanelo’s posts), the popular tradition assigns its brought to Toledo from Orgaz exclusively to the work carried out by Juanelo and his daughter, “in spite of the fact that they are columns 75 feet long and 5 feet in diameter”.

The posts remained close to the quarry until they were taken to form part of the basilica built by dictator Francisco Franco in the place known as “Cuelgamuros”, after the Spanish Civil War (Valley of the Fallen). The current measurements of these monoliths are 11.50 meters high and 1.50 meters wide each. A copla is said in Orgaz in this respect:

they’re already walking,

will come to your site

God knows when.”

Once again we see how history mistreats the greatest geniuses humanity has ever had: Juanelo did not see a single duchy of this complex work done in duplicate.

He died totally ruined in 1585 at the age of 85 with large debts owed to his suppliers and saved from the Inquisition, according to some chroniclers, by the grace of His Majesty. His daughter and grandchildren continued to take care of the maintenance of the two artifices, living badly with a pension given to them by Philip III.

I’m sure you’re also interested in: Legend of the Stick Man, children’s version

Various models of the artifice have been exhibited in recent years. Even in a press release has been proposed again the construction of this, for tourist purposes (the water of the Tagus is terribly polluted)

An old legend from Toledo affirms that another of Juanelo’s wonderful creations was “El Hombre de Palo” (The Man of the Stick), an automaton that circulated in the street that now has the same name and that every day he would walk through the centre of Toledo begging for some money to allow an old man Juanelo to eat every day.

An old legend from Toledo affirms that another of Juanelo’s wonderful creations was “El Hombre de Palo” (The Man of the Stick), an automaton that circulated in the street that now has the same name and that every day he would walk through the centre of Toledo begging for some money to allow an old man Juanelo to eat every day.

The importance of the artifice, in spite of all the problems, made that some years later, Lope de Vega, in his “Lover grateful” limited to two the masterpieces of Toledo:

I will see the Major Church, of Juanelo the artifice…”

Bibliography:

- Enríquez de Salamanca, Cayetano: “Curiosidades de Toledo” Ed. El País Aguilar (1992)

On the Internet:

On the Web you can find extensive information about Juanelo Turriano; here are some links that in turn lead to more extensive information:

- Much of the information is held in the custody of the Juanelo Turriano Foundation: www.juaneloturriano.com

- Interesting Millennium 3 program dedicated to Juanelo Turriano.

- “Clockwork Prayer: A Sixteenth-Century Mechanical Monk”, a large studio dedicated to Juanelo and mechanical devices, with photos.

- Juanelo Turriano, a man ahead of his time.

- Digital reconstruction of the Artificio de Juanelo.

- Julio Porres de Mateo: “Juanelo’s artifice”

- “El Artificio de Juanelo” Peces Ventas, Juan Luis

- Orgaz, data and customs.

* Old engraving: http://www.grabadoantiguo.com (you can purchase hundreds of old engravings on this magnificent website, including quite a few high quality Toledo engravings)