The king of Castile marched to the Moorish war, and to fight with the enemies of religion had appealed in war to all the most flowery of the nobility of their kingdoms.

The king of Castile marched to the Moorish war, and to fight with the enemies of religion had appealed in war to all the most flowery of the nobility of their kingdoms. The silent streets of Toledo resounded night and day with the martial rumour of the atabales and the clarines, and already in the Moorish door of Bisagra, already in that of Valmardón or in the embouchure of the old bridge of San Martín, no hour passed without the hoarse shout of the sentinels announcing the arrival of some knight who, preceded by his stately banner and followed by riders and pawns, came to meet the bulk of the Castilian army.

The king of Castile marched to the Moorish war, and to fight with the enemies of religion had appealed in war to all the most flowery of the nobility of their kingdoms. The silent streets of Toledo resounded night and day with the martial rumour of the atabales and the clarines, and already in the Moorish door of Bisagra, already in that of Valmardón or in the embouchure of the old bridge of San Martín, no hour passed without the hoarse shout of the sentinels announcing the arrival of some knight who, preceded by his stately banner and followed by riders and pawns, came to meet the bulk of the Castilian army.

The time that was left to undertake the way of the frontier and to conclude to order the royal hosts ran in the middle of public celebrations, luxurious convites and lucid tournaments, until, arrival, at last, the eve of the day indicated beforehand by his highness for the exit of the army, a last sarao was arranged, with which they should finish the rejoicing.

The night of the sarao, the fortress of the kings offered a singular aspect. In the wide courtyards, around immense bonfires and scattered without order or concert, there was a variegated multitude of pages, soldiers, crossbowmen and small people, that these dressing their corceles and their weapons and arranging them for the combat; those greeting with shouts or blasphemies the unexpected turns of fortune, personified in the dice of the cubilete; the others repeating in chorus the proverb of a romance of war that intoned a juggler, accompanied by the guzla, accompanied by the guzla; Those from beyond, buying from a rosemary shells, crosses and ribbons played in the sepulchre of Santiago, or laughing with crazy laughter at the jokes of a buffoon, or rehearsing in the bugles the warlike air to enter the fight, proper to their lords, or referring to ancient stories of chivalrying or adventures of love, or miracles recently occurred, formed an infernal and thunderous whole, impossible to paint with words.

Above that scrambled ocean of war songs, rumor of hammers hitting the anvils, chirps of limes biting steel, steeds piafar, broken voices, inextinguishable laughter, out of tune screams, intemperate notes, oaths and strange and discordant sounds, floated at intervals, like a breath of harmonious breeze, the distant chords of the music of sarao.

This one, which took place in the halls that formed the second body of the fortress, offered, in turn, a picture, if not so fantastic and capricious, more dazzling and magnificent.

For the extensive galleries that extended in the distance, forming an intricate labyrinth of slender pilasters and openworked warheads and light as lace; Through the spacious rooms dressed in tapestries, where silk and gold had represented with a thousand different colours, scenes of love, hunting and war, and adorned with trophies of weapons and shields, over which poured a sea of sparkling light a countless number of lamps and chandeliers of bronze, avocado and gold, hung those of the highest vaults and nailed these in the thick ashlars of the walls; Everywhere where eyes turned, a cloud of beautiful ladies with rich gold-plated garments, nets of pearls imprisoning their curls, jewels of rubies flaming on their breast, feathers held in a vaporous fence to an ivory handle, hung by the fist, could be seen swaying and waving in different directions, and rostrillos of white lace that caressed their cheeks, or happy mobs of gallants with talabartes of velvet, justillos of brocade and tights of silk, borceguíes of tafilete, capotillos of lost sleeves and caperuza, daggers with knob of filigree and estoques of cut, burnished, thin and light.

But among this brilliant and dazzling youth, that the elders watched parading with a smile of joy, seated in the high larch seats that surrounded the royal dais, a woman, acclaimed queen of beauty in all the tournaments and courts of love of the time, attracted attention for her incomparable beauty, whose colours had been adopted by company by the bravest knights, whose charms were a matter of the coplas of the troubadours most versed in the science of gay knowledge, to which all eyes turned with astonishment, for which all hearts secretly sighed; around which the most illustrious offspring of the nobility of Toledo, gathered in the sarao of that night, could be seen gathered with eagerness, like humble vassals around their lady.

Those who attended continuously to form the retinue of presumed galanes of Doña Inés de Tordesillas, that such was the name of this celebrated beauty, in spite of its haughty and disdainful character, never fainted in its pretensions; and this one animated with a smile that had believed to guess in its lips, that one with a benevolent look that judged to have surprised in its eyes; the other one, with a flattering word, a very light favor or a remote promise, each one waited in silence to be the preferred one; the other, with a flattering word, a very light favor or a remote promise, each one waited in silence to be the preferred one. However, among all of them there were two that were more particularly distinguished by their assiduity and performance, two that, apparently, if not the favorite of the beautiful, could be qualified as the most advanced in the path of their heart. These two knights, equal in cradle, value and noble garments, servants of the same king and suitors of the same lady, were called Alonso de Carrillo, one, and Lope de Sandoval, the other.

Both had been born in Toledo; together they had made their first weapons, and in the same day, when their eyes met those of Doña Inés, they felt possessed of a secret and ardent love for her, love that germinated some time withdrawn and silent, but that at the end began to be discovered and to give involuntary signs of existence in their actions and speeches.

In the tournaments of Zocodover, in the floral games of the court, whenever they had been presented with a juncture to rival each other in gallantry or donaire, both knights, eager to distinguish themselves in the eyes of their lady, had taken advantage of it with eagerness; And that night, impelled, no doubt, by the same eagerness, exchanging irons for feathers and meshes for brocades and silk, standing next to the seat where she reclined a moment after having walked around the halls, they began an elegant struggle of ingenious and enamored phrases, embossed and sharp epigrams.

The minor stars of this brilliant constellation, forming a golden semicircle around the two gallants, laughed and strained the delicate jokes; and the beautiful object of that tournament of words approved with an imperceptible smile the concepts chosen or full of intention that ora came out of the lips of their adorers like a light wave of perfume that flattered their vanity, Ora departed like a sharp arrow that was going to look for, to nail itself in him, the most vulnerable point of the opposite: its self-love.

Already the courteous combat of ingenuity and gallantry began to become more and more crude; the phrases were still polite in form, but brief, dry, and when pronouncing them, although they were accompanied by a slight dilation of the lips, similar to a smile, the light flashes of the eyes impossible to hide, demonstrated that the anger boiled compressed in the bosom of both rivals.

The situation was unsustainable. The lady understood it thus, and rising from the seat she was preparing to return to the halls, when a new incident came to break the fence of the respectful restraint in which the two young lovers were contained. Perhaps with intention, perhaps by carelessness, Doña Inés had left on her skirt one of the perfumed gloves, whose golden buttons were entertained in tearing one by one while the conversation lasted. As he stood up, the glove slipped through the wide silk folds and fell on the carpet. Seeing him fall, all the knights who formed his shining entourage quickly leaned in to pick him up, disputing the honor of achieving a slight nod in prize from their gallantry.

Noticing the haste with which everyone made the gesture of bowing, an impeccable smile of satisfied vanity appeared on the lips of the proud Doña Inés, who after making a general greeting to the gallants who showed such determination to serve her, without looking hardly and with a high and contemptuous look, reached out her hand to pick up the glove in the direction in which Lope and Alonso, the first who seemed to have reached the place where it fell, were.

In fact, both young men had seen the glove fall close to their feet; both had inclined with equal haste to pick him up, and when they joined up, each had it grasped at one end. Seeing them immobile, silently defying themselves with their gaze, and both determined not to abandon the glove they had just lifted from the ground, the lady let out a slight and involuntary cry, which drowned out the murmur of the astonished spectators, who sensed a stormy scene which in the fortress, and in the presence of the king, could be described as a horrible disrespect.

Nevertheless, Lope and Alonso remained impassive, mute, measuring themselves with their eyes, from head to toe, with the tempest of their souls revealed only by a slight nervous tremor that shook their limbs as if they were attacked by a sudden fever.

The murmurs and the exclamations were rising of point; the people began to group around the actors of scene; Doña Inés, or stunned or being pleased in prolonging it, was turning from a side to another one, like looking for refuge and to avoid the looks of the people, that every time went in greater number. The catastrophe was already certain; the two young men had already changed some words in a deaf voice, and while with one hand they held the glove with a convulsive force, they seemed to instinctively seek with the other the golden fist of their daggers, when the group formed by the spectators opened respectfully and the king appeared.

His forehead was serene; there was no indignation in his face, nor wrath in his gesture.

He glanced around, and this one gaze was enough to let him know what was going on. With all the gallantry of the most accomplished maiden, he took the glove from the hands of the knights, who, as if moved by a spring, opened themselves without difficulty to feel the contact of the monarch and turning to doña Inés de Tordesillas, who leaned on the arm of a landlady seemed about to faint, exclaimed, presenting him, with an accent, although tempered, firm:

.

-Take it, madam, and be careful not to let it fall on another occasion where, when you return it to them, they will return it to you stained in blood.

When the king finished saying these words, Doña Inés, we will not be able to say whether she had vanished in the arms of those who surrounded her.

Alonso and Lope, the one squeezing silently between their hands the velvet hat, whose feather dragged by the carpet, and the other biting his lips to make the blood sprout, nailed a tenacious and intense look.

A glance at that cast amounted to a slap, a glove thrown in the face, even a defiance to death. At midnight, the kings retreated to their chamber. The sarao ended, and the curious of the people, who were waiting impatiently for this moment forming groups and corrillos in the avenues of the palace, ran to park on the slope of the Alcázar, the Miradores and the Zocodover.

For one or two hours, in the streets immediately surrounding these points, a bustle, an animation and an indescribable movement reigned. Everywhere you could see squires caracoleando crossing in their richly harnessed steeds, kings of arms with luxurious chasubles full of shields and coats of arms, timbaleros dressed in bright colors, soldiers covered with shining armor, pages with velvet hoods and caps crowned with feathers, and servants on foot who preceded the luxurious bunk beds and the walkways covered with rich cloths, carrying in their hands large lighted axes, whose reddish glow could be seen the multitude that, with astonished face, half-opened lips and frightened eyes, watched with astonishment the best of the Castilian nobility parade, surrounded on that occasion by a fabulous fausto and splendour.

Then, little by little, the noise and the animation ceased; the stained glass of the high warheads of the palace let shine; the last cavalcade went through the crowded groups; The people of the village, in their turn, began to disperse in all directions, losing themselves in the shadows of the tangled labyrinth of dark, narrow and crooked streets, and the deep silence of the night was no longer disturbed except by the distant cry of a warrior’s candle, the rumour of the steps of some curious person who withdrew the last one, or the noise produced by the albadas of some doors as they closed, when a knight appeared at the top of the staircase leading to the palace platform, who, after looking all over, as if looking for someone to wait for him, descended slowly towards the slope of the fortress, by which he went towards the Zocodover.

When he reached the square of this name, he stopped for a moment and looked around him again. The night was dark; not a single star shone in the sky, not a single light could be seen in the whole square, yet there in the distance, and in the same direction in which a slight sound of approaching steps began to be perceived, he thought he could distinguish the bundle of a man: no doubt, the same one who seemed to be waiting so impatiently.

The knight who had just left the fortress to go to Zocodover was Alonso Carrillo, who, because of the position of honor he held near the person of the king, had had to accompany him in his chamber until those hours. Lope de Sandoval, who came out of the shadows of the arches surrounding the square to meet him. When the two knights had met, they changed a few sentences quietly.

-I presumed you were waiting for me,” said the one.

-I was hoping you’d brag about it,” replied the other.

-And where shall we go?

-Anywhere where four palms of ground can be found to be stirred and a ray of light that illuminates us.

At the end of this very brief dialogue, the two young men went into one of the narrow streets that lead to the Zocodover, disappearing into the darkness like those ghosts of the night that, after terrifying for an instant the one who sees them, break into atoms of fog and become confused in the bosom of the shadows.

For a long time they wandered through the streets of Toledo, looking for a place on purpose to end their differences; but the darkness of the night was so deep, that the duel seemed impossible. However, both wished to fight, and to fight before dawn, for at dawn the royal armies must depart, and Alonso with them.

They went on, then, randomly crossing deserted squares, shady passageways, narrow and dark alleys, until, finally, they saw a light shining in the distance, a small and dying light, around which the fog formed a fence of fantastic and doubtful clarity.

I’m sure you’re also interested: Don Diego de la Salve

They had reached the street of Christ, and the light that could be seen at one end seemed to be that of the lantern that illuminated at that time, and still illuminates the image that gives its name.

When they saw her, they both let out a jubilant exclamation and, hastening the step in her direction, they soon found themselves next to the altarpiece in which she was burning.

An arch sunk in the wall, at the back of which was seen the image of the Redeemer nailed to the cross and with a skull at the foot; a rough shed of boards that defended him from the elements, and the small lantern hung from a rope, which illuminated him weakly, hesitating at the impulse of the air, formed the whole altarpiece, around which hung some festoons of ivy that had grown between the dark and broken ashlars, forming a kind of vegetable pavilion.

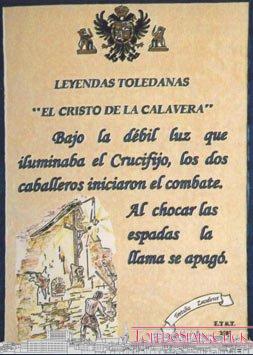

The knights, after respectfully saluting the image of Christ by taking off their caps and whispering a short prayer in a low voice, recognized the terrain with a glance, grounded their cloaks, and preparing each other for combat and giving each other the signal with a slight nod, crossed the stocks.

But the steels had barely been touched, and before any of the fighters could have taken a single step or attempted a blow, the light suddenly went out and the street was plunged into the deepest darkness.

As if guided by the same thought, and surrounded by sudden darkness, the two combatants took a step back, lowered their swords and raised their eyes towards the lantern, whose light, moments before extinguished, shone again to the point where they made a gesture to suspend the fight.

-It must be some blast of air that knocked down the flame as it passed,” exclaimed Carrillo, once again putting himself on guard and warning Lope, who seemed worried, with a voice.

Lope took a step forward to recover the lost ground, stretched out his arm and the steels touched again; but, upon touching each other, the light turned itself off, remaining so until the stocks were separated.

-This is strange indeed,” Lope muttered, looking at the lantern, which had spontaneously ignited again and was rocking slowly in the air, pouring a strange, trembling light on the yellow skull of the skull placed at the feet of Christ.

-” Bah!” said Alonso. She will be the blessed one in charge of taking care of the lantern of the altarpiece, arming the devotees and the oil is scarce, by which the light, close to death, shines and darkens at intervals in agony.